Runtime: 93 minutes

Currently on Netflix: Yes

Currently on Indieflix: No

IMDb page: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1286537/?ref_=ttawd_awd_tt

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5eKYyD14d_0

Robert Kenner’s Oscar-nominated Food Inc. is one of those documentaries that gets me fired up no matter how many times I watch it, so please bear with me if this review morphs into a rant about the government. As someone interested in health and nutrition, I sometimes settle in to the idea that everyone has the choice of what food to eat, and that all one has to do to become healthy is eat a higher healthy fat, low-carb diet with foods from quality sources. It should be so simple, right? In a perfect world, maybe. But this is not a perfect world because I do not drive a Ferrari to work or own a unicorn that poops out grass-fed, organic cheeseburgers. Unfortunately, we live in a world with a government that was formed to protect the people but has instead been corrupted by large corporations, putting profits ahead of the health and livelihood of its people. Food, Inc. discusses the dishonesty fed to us in every step of food production even before the seed is planted in the ground or the chicken is hatched from the egg, and it does so with a barrage of stunning statistics that opens the viewer’s eyes a little wider with each one.

The film begins by interviewing Eric Schlosser, investigative journalist and author of Fast Food Nation. He explains that the vast majority of food companies are controlled by about half a dozen large corporations—corporations that keep their farmers so far in debt and fear that even the most ethical farmer is forced to grow chickens that can’t stand because they are too sick and fat, or risk a lawsuit they have no chance of winning. Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, then discusses the history and current uses of one of America’s favorite crops: corn. Farmers are subsidized and encouraged to grow as much corn as possible because it can be used to make all kinds of sweeteners, fuels, building materials, and, most disturbingly, animal feed. It is well known that cows and fish were never meant to eat corn and yet the majority are, which causes countless health problems in the animals and even in humans.

One of these health problems is caused by E. coli O157:H7, a strain of E. coli resistant to a cow’s stomach acids meaning it ends up in their feces and, in turn, ground beef. It is a strain that was never meant to exist in humans, yet by feeding cows food they weren’t meant to eat it was created, strengthened and introduced into the human population. In 2001, this virus killed a two-year-old named Kevin, a perfectly healthy boy who ate a hamburger while on vacation and died twelve days later of kidney failure. His mother, Barbara, is now a food safety advocate and is working hard to enact Kevin’s Law, which would allow the USDA to shut down processing plants that repeatedly produce contaminated food. This no-brainer law has not been passed thanks to lobbying from meat processors, though some aspects have been adopted into Obama’s 2011 FSMA Law.

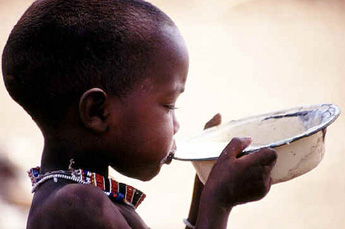

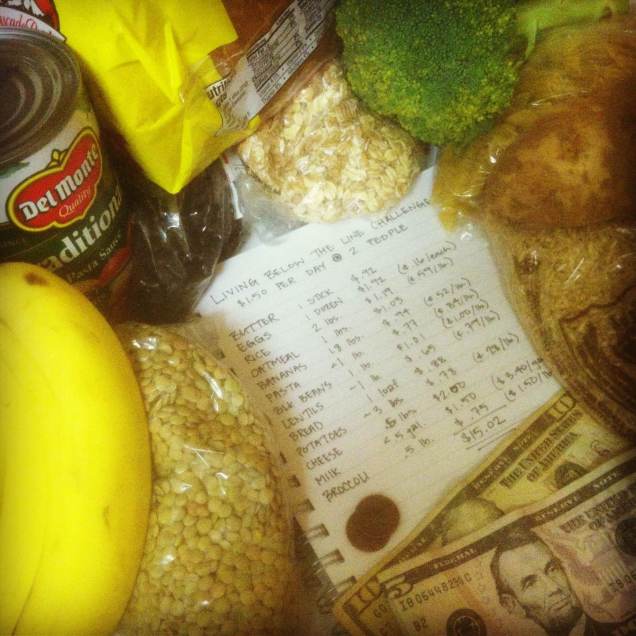

The film then briefly investigates the correlation between obesity and income level, a relationship that shouldn’t be too surprising considering a cheeseburger at McDonalds costs less than many vegetables at the grocery store. This is in part because the foods that make the cheeseburger so unhealthy— corn and corn-based products, for example— are subsidized by the government. This leads to low-income families, who often work longer hours and have less time to cook or shop for healthy food, to go through the drive-thru or not eat at all (a fact not mentioned in the film is that there is a higher density of fast-food restaurants in lower-income housing areas—coincidence?)

The last sections of the film focus on the government tactics used to increase profits and control the agriculture and farming industry. A farmer who raises grass-fed animals explains that the government has tried shutting down his farm because of “unsanitary conditions” (he processes chickens by hand in an open-air shelter in his field, for example), which is odd because his chicken was tested at a local lab against store-bought chicken and was found to have 27x less harmful bacteria. He then discusses a 1980 Supreme Court ruling that allowed companies to patent genetically-modified organisms and fueled many biotechnology companies, namely Monsanto, to create GMO crops and then control farmers who use those crops through threats of patent infringement lawsuits. These companies can even investigate and sue farmers who never bought GMO seeds if some have blown into their field from a neighboring farm without them knowing. The film then discusses several key players in Monsanto’s strong grasp in the government including Monsanto attorney-turned Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, members of the Clinton and Bush administration, and several members of the USDA and FDA.

Just as I was feeling the overwhelming urge to punch a Monsanto lawyer in the face, the documentary ends with a short glimmer of hope. The conclusion reminds us that with every news story of salmonella or E. coli, and every documentary like Food Inc. (there are many), the curtain covering up the corruption in the food industry is slowly being pulled away, informing consumers who are then better able to vote with their dollar by purchasing local produce and food if possible. It cites the changes in the tobacco industry over the past few decades as evidence that the food industry can similarly improve.

This is another documentary that we watched before filming our own, and was the film I personally kept most in the back of my mind while filming and editing. Though our film focuses mostly on the labor behind the food, while Food Inc. focuses on the government corruption influencing food quality and safety, there is a short section in the film about the large corporation Smithfield arranging with government agencies to only arrest and deport a small number of illegal immigrant workers every night to satisfy the need for deportations with little impact to their workforce.

I couldn’t cover everything I wanted because the film is so densely packed with important information—all I can say is you just have to watch it. I highly recommend this documentary to anyone and everyone, especially those interested in food and health. No matter how many times I watch it I still find myself feeling depressed and angry at the government afterwards. The genius of this film is that I feel these things without the film even grazing the surface of animal rights and humane slaughtering practices— it doesn’t need to because your jaw is already on the floor without these. Funny enough, after watching the movie I had to cook some chicken breasts to bring to work and I just stared at them for a few minutes, glaring at the picture of a happy little farm on the package and thinking about how this chicken probably wasn’t an animal—just a fat, sickly blob of meat who couldn’t walk two steps.

Cinematography: 9/10 From the beginning, you see helicopter shots of rolling fields and smooth panning shots in a large grocery store. Knowing how hard it is to get permission to do these things (having tried myself with our film), I was impressed.

Soundtrack: 9/10 The music helped to elicit emotions; for example, during tense scenes involving the lawsuits between farmers and these corporations the music became dramatic and suspenseful.

Editing: 10/10 The structure of the film was easy to follow. The animations at the beginning explaining the companies who control meat processing or the difference between a chicken of the 1950’s and a chicken today were very well done, and again having tried doing creative animations like this in our own film (having to finally resort to kinetic typography) I was very impressed.

Impact: 10/10 If I could rate this one any higher I would (I guess I could since I made the scoring system, but I’ll resist the urge). This is an issue that affects everyone no matter their income level, race, or any other lifestyle characteristic. Anyone who eats food (which should be everyone) is affected by the laws and actions of the government AND has the power to improve the system.

Overall: 9.5/10

Remember, we love discussion about movies! If you have an opinion about this film, or know of a documentary we should review, email us at bsberries@gmail.com or hit us up on Twitter or Facebook.

-Scott Hines

Scott Hines is a Director for Blood, Sweat and Berries.